Expert Opinion Project: Collaborative Wisdom (2025-2027)

Brief overview

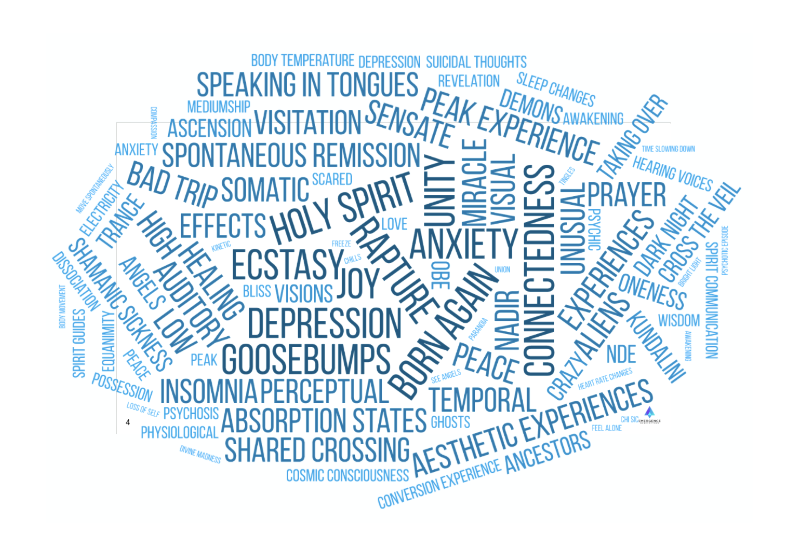

The Expert Opinion Project project seeks to bridge the gaps between clinical practice and what we call emergent phenomena, experiences and effects (EPEE; Sandilands & Ingram, 2024) – the deep end of human experience and development, often labelled as spiritual, meditative, mystical, magical, psi, psychedelic, or energetic – drawing on collaborative expertise and wisdom to improve global medical and mental healthcare.

Building on insights from our recently completed pilot study, the Expert Opinion Project: Collaborative Wisdom (2025-2027) will bring together 60 experts from diverse cultures and ontological frameworks (including psychiatrists, neurologists, meditation teachers, traditional healers, psychedelic therapists, and practitioners bridging multiple worlds) to co-create:

- Deeper understanding of the clinical relevance and transformative potential of emergent phenomena

- The beginnings of a professional lexicon to facilitate clearer clinical understanding and communication

- Consensus-based guidance and practical tools for identifying what is happening when someone is experiencing emergent phenomena and offering appropriate support

All findings, tools, and educational materials will be freely available online in at least three languages, reflecting our commitment to open-source global collaboration.

If you’re interested in participating in the study and you would like to receive the Expression of Interest form, please reach out to our email: eop@ebenefactors.org. You are also welcome to request this form in another language.

This project is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Background

EPEEs encompass a wide range of experiences that may manifest across multiple domains, including (but not limited to):

- perceptual (such as visionary experiences or endogenous light phenomena),

- somatic (including energy-like sensations, involuntary movements, or shifts in body schema),

- cognitive (involving altered thinking patterns or reality testing),

- emotional (ranging from profound bliss to existential terror),

- existential (fundamental changes to one’s sense of self, worldview, or connection to the universe).

These phenomena are surprisingly common (Wright et al., 2024), and given their potential symptomatic overlap with mental and medical conditions, they may be easily misunderstood, especially in clinical settings.

Outside of Western medical contexts these experiences may be recognized as a normal part of healthy spiritual development. For example, renowned meditation teacher and clinical psychology PhD Jack Kornfield (1979) reported over 45 years ago that experienced meditation practitioners commonly undergo a wide range of sensory and perceptual alterations, including transient hallucinations. In some contexts emergent experiences may also be associated with long-lasting positive impacts, including enhanced emotional well-being, resilience, sense of connection, and belonging (e.g., Horton, 1973; Corneille & Luke, 2021). There remains little scientific understanding of why these experiences arise or how they intersect with medical or mental health conditions, though cultural interpretation and approach is thought to play a critical role in determining whether they unfold as growth-promoting experiences or become sources of distress (Luhrmann et al., 2024).

The current gap in clinical understanding means that individuals undergoing potentially profound and transformative developmental processes may be misunderstood and receive pathologizing responses rather than supportive guidance, leading to suboptimal outcomes.

According to Sandilands & Ingram (2024), EPEEs can arise spontaneously, though they often arise through intentional practices such as meditation, psychedelics, yoga, breathwork, prayer, or others. As consciousness-altering practices such as yoga and meditation surge in popularity globally (Masci & Hackett, 2018), and regions such as Colorado and Washington DC decriminalize potent psychedelics such as psilocybin, this discrepancy between clinical understanding and collective prevalence of EPEEs is increasingly dangerous.

Current status

IRB approval pending.

Research team

Dr. Daniel M. Ingram, Co-Principal Investigator

Dr. Hannah Biddell, Co-Principal Investigator

Beata Grobenski, Research Associate

Steven Egan, Project Manager

Relevant research publications

- Brook, M. G. (2021). Struggles reported integrating intense spiritual experiences: Results from a survey using the Integration of Spiritually Transformative Experiences Inventory. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 13(4), 464.

- Clarke, I. (Ed.). (2010). Psychosis and spirituality: Consolidating the new paradigm. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cook, C. C., & Powell, A. (Eds.). (2022). Spirituality and psychiatry. Cambridge University Press.

- Cooper, D. J., Lindahl, J. R., Palitsky, R., & Britton, W. B. (2021). “Like a Vibration Cascading through the Body”: Energy-Like Somatic Experiences Reported by Western Buddhist Meditators. Religions, 12(12), 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121042

- Corneille, J. S., & Luke, D. (2021). Spontaneous spiritual awakenings: phenomenology, altered states, individual differences, and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720579

- Elendu, C. (2024). The evolution of ancient healing practices: From shamanism to Hippocratic medicine: A review. Medicine, 103(28), e39005.

- Grabovac, A. (2015). The stages of insight: Clinical relevance for mindfulness-based interventions. Mindfulness, 6(3), 589-600.

- Horton, P. C. (1973). The mystical experience as a suicide preventive. American Journal of Psychiatry, 130(3), 294-296.

- Kornfield, J. (1979). Intensive insight meditation: A phenomenological study. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 11(1), 41.

- Lindahl, J. R., & Britton, W. B. (2019). “I have this feeling of not really being here”: Buddhist meditation and changes in sense of self. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 26(7–8), 157–183.

- Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K., & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PloS one, 12(5), e0176239.

- Lucchetti, G., Bassi, R. M., & Lucchetti, A. L. G. (2013). Taking spiritual history in clinical practice: a systematic review of instruments. Explore, 9(3), 159-170.

- Luhrmann, T. M., Dulin, J., & Dzokoto, V. (2024). The shaman and schizophrenia, revisited. Culture, medicine, and psychiatry, 48(3), 442-469.

- Lukoff, D. (2007). Visionary spiritual experiences. SOUTHERN MEDICAL JOURNAL-BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA-, 100(6), 635.

- Lukoff, D., Lu, F., & Turner, R. (1992). Toward a more culturally sensitive DSM-IV: Psychoreligious and psychospiritual problems. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 180(11), 673-682.

- Masci, D., & Hackett, C. (2018). Meditation is common across many religious groups in the US.

- Milliere, R. (2020). Varieties of Selflessness. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 1(I), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.33735/phimisci.2020.I.48

- Menezes Júnior, A. D., & Moreira-Almeida, A. (2009). Differential diagnosis between spiritual experiences and mental disorders of religious content. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 36, 75-82.

- Moreira-Almeida, A., Koenig, H. G., & Lucchetti, G. (2014). Clinical implications of spirituality to mental health: review of evidence and practical guidelines. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria, 36(2), 176-182.

- Moreira‐Almeida, A., Sharma, A., van Rensburg, B. J., Verhagen, P. J., & Cook, C. C. (2016). WPA position statement on spirituality and religion in psychiatry.

- Puchalski, C. M. (2010). Formal and informal spiritual assessment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 11(Suppl 1), 51-57.

- Sanabria, E. (2025). Science’s “Savage Slot”: the appropriation and erasure of Indigenous science in the psychedelic renaissance. Psychedelics, 100003.

- Sandilands, O., & Ingram, D. M. (2024). Documenting and defining emergent phenomenology: theoretical foundations for an extensive research strategy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1340335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1340335

- Spittles, B. (2023). Better understanding psychosis: Psychospiritual considerations in clinical settings. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 63(2), 246-254.

- Vieten, C., Scammell, S., Pilato, R., Ammondson, I., Pargament, K. I., & Lukoff, D. (2013). Spiritual and religious competencies for psychologists. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(3), 129.

- Vieten, C., Scammell, S., Pierce, A., Pilato, R., Ammondson, I., Pargament, K. I., & Lukoff, D. (2016). Competencies for psychologists in the domains of religion and spirituality. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(2), 92.

- Vieten C, Wahbeh H, Cahn BR, MacLean K, Estrada M, Mills P, et al. (2018) Future directions in meditation research: Recommendations for expanding the field of contemplative science. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0205740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205740

- Volkan, V. D. (2015). Fragments of trauma and the social production of suffering: Trauma, history, and memory.

- Wildman, W. J. (2025). Spirituality is older than religion: Supporting the phylogenetic primacy of intensity over religiosity using the PCI-RSE. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 00846724251334672.

- Wright, M. J., Galante, J., Corneille, J. S., Grabovac, A., Ingram, D. M., & Sacchet, M. D. (2024). Altered states of consciousness are prevalent and insufficiently supported clinically: A population survey. Mindfulness, 15(5), 1162-1175.

Get involved

Learn more about us

The Expert Opinion Project, supported by Emergence Benefactors, is part of the White Paper of the Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium (EPRC). To learn more about the EPRC visit here:

The Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium (EPRC) and our mission

Donate

Donate to Emergence Benefactors (US 501(c)(3) charitable organization)

Find us on social media

Send us an email

FAQs

- What are emergent phenomena?

Emergent phenomena, experiences and effects (EPEEs) are experiences often interpreted or labelled as spiritual, mystical, energetic, psychedelic, or magical in nature (see Sandilands & Ingram, 2024 for extended definition) that may lead to transformative outcomes and be more prevalent than previously thought. For example, Wright et al. (2024) found that 45% of participants in a general population study reported experiencing non-pharmacologically induced EPEE at least once in their lives, with higher rates under the influence of mind-altering substances.

According to Sandilands and Ingram (2024), these experiences include but are not limited to:

- deep absorption states (Sparby and Sacchet, 2024),

- energy-like somatic experiences and involuntary movements (Cooper et al., 2021),

- shifts to body schema (Ataria et al. 2015),

- heightened basic wakefulness (Britton et al., 2014),

- endogenous light perceptions (Lindahl et al., 2014),

- visionary experiences (Lukoff, 2007),

- profound altered states resulting in emotional, behavioural, existential, ontological and paradigmatic shifts, such as deep changes to sense of self and one’s connection to the universe (Corneille and Luke, 2021; Lindahl and Britton, 2019; Millière et al., 2018; Millière, 2020) and profound vocational and life-trajectory impacts (Nicholson, 2014).