Expert Opinion Project: A Pilot Study

Brief overview

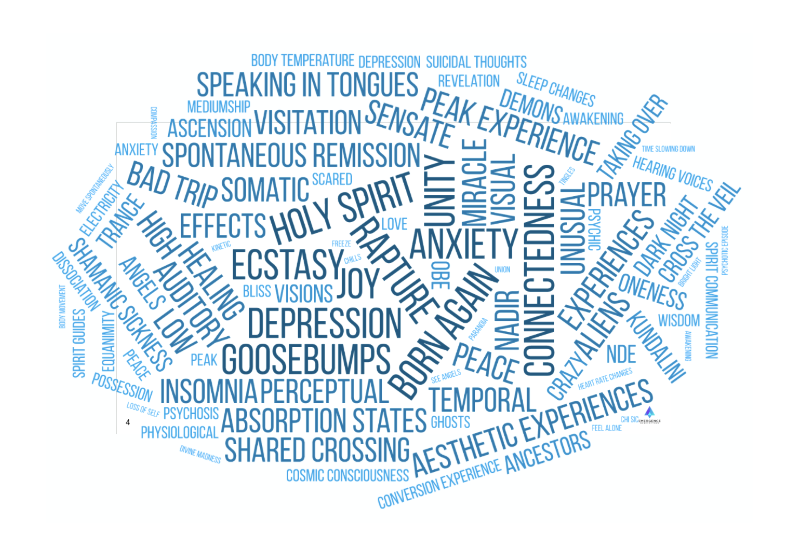

The Expert Opinion Project project seeks to bridge the gaps between clinical practice and what we call emergent phenomena, experiences and effects (EPEE; Sandilands & Ingram, 2024) – the deep end of human experience and development, often labelled as spiritual, meditative, mystical, magical, psi, psychedelic, or energetic – drawing on collaborative expertise and wisdom to improve global medical and mental healthcare.

Background

EPEEs encompass a wide range of experiences that may manifest across multiple domains, including (but not limited to):

- perceptual (such as visionary experiences or endogenous light phenomena),

- somatic (including energy-like sensations, involuntary movements, or shifts in body schema),

- cognitive (involving altered thinking patterns or reality testing),

- emotional (ranging from profound bliss to existential terror),

- existential (fundamental changes to one’s sense of self, worldview, or connection to the universe).

These phenomena are surprisingly common (Wright et al., 2024), and given their potential symptomatic overlap with mental and medical conditions, they may be easily misunderstood, especially in clinical settings.

Outside of Western medical contexts these experiences may be recognized as a normal part of healthy spiritual development. For example, renowned meditation teacher and clinical psychology PhD Jack Kornfield (1979) reported over 45 years ago that experienced meditation practitioners commonly undergo a wide range of sensory and perceptual alterations, including transient hallucinations. In some contexts emergent experiences may also be associated with long-lasting positive impacts, including enhanced emotional well-being, resilience, sense of connection, and belonging (e.g., Horton, 1973; Corneille & Luke, 2021). There remains little scientific understanding of why these experiences arise or how they intersect with medical or mental health conditions, though cultural interpretation and approach is thought to play a critical role in determining whether they unfold as growth-promoting experiences or become sources of distress (Luhrmann et al., 2024).

The current gap in clinical understanding means that individuals undergoing potentially profound and transformative developmental processes may be misunderstood and receive pathologizing responses rather than supportive guidance, leading to suboptimal outcomes.

According to Sandilands & Ingram (2024), EPEEs can arise spontaneously, though they often arise through intentional practices such as meditation, psychedelics, yoga, breathwork, prayer, or others. As consciousness-altering practices such as yoga and meditation surge in popularity globally (Masci & Hackett, 2018), and regions such as Colorado and Washington DC decriminalize potent psychedelics such as psilocybin, this discrepancy between clinical understanding and collective prevalence of EPEEs is increasingly dangerous.

Study goals

Our study aims to address this gap by developing preliminary guidelines for the recognition and appropriate support of EPEEs, preparing clinicians to more effectively respond to the rising number of patients presenting with EPEEs. By working with a panel of international experts, whose expertise ranges from psychiatry to indigenous healing, we aim to ensure that a diverse range of expertise around understanding and managing these phenomena are heard, respected, and valued in the development of these clinical guidelines.

Looking to the future, this project aims not only to address immediate needs in clinical practice, but also anticipate how emergent phenomena will play an increasing role in the future healthcare.

Study design

The study consisted of three rounds of expert surveys, culminating in a final quantitative consensus measurement to assess agreement with the formulated conclusions and guideline recommendations.

A Delphi methodology was chosen for this study because it provides a structured approach to synthesizing diverse opinions on complex topics where empirical evidence is currently insufficient. The iterative nature of the Delphi process allows for systematic refinement of ideas and identification of areas of agreement and disagreement among experts with varied backgrounds, which is particularly valuable for understanding multifaceted experiences that can cross traditional disciplinary boundaries.

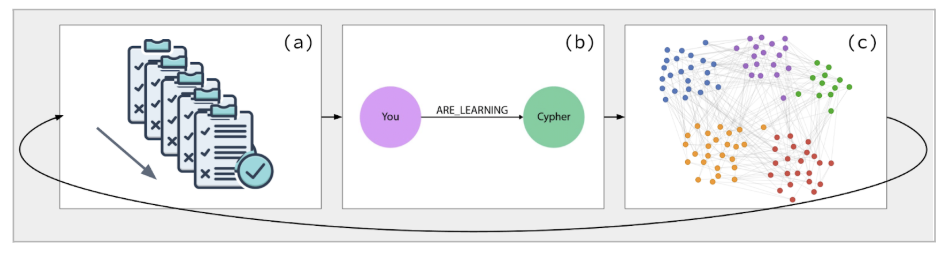

This study uses an AI-augmented Delphi methodology → an iterative consensus-building process:

- using structured surveys

- administered to a multidisciplinary panel of experts, and

- leveraging LLMs to programmatically create structured encodings of questionnaire responses.

These encoded representations of the collective responses are then iterated back to the experts for subsequent Delphi rounds, thus facilitating consensus-building and integrated understanding (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1: AI-augmented Delphi process

Analysis technique

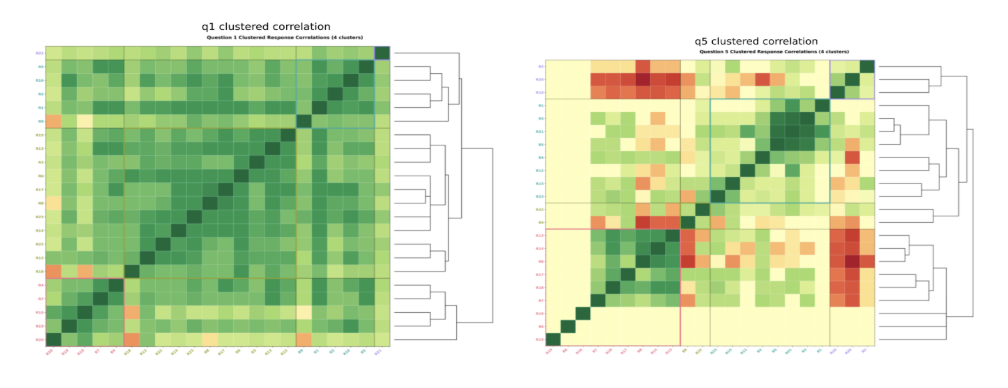

The core quantitative analysis leverages AI to generate pairwise correlation matrices between expert responses for each question. For every possible pair of experts (n² total comparisons), Claude evaluates conceptual alignment on a scale from -1.0 (complete disagreement) to 1.0 (complete agreement). To enhance reliability, we implement triple-redundant scoring with averaging for each pair. These correlation matrices are visualized as color-coded heatmaps, revealing patterns of agreement and disagreement (see figure 2, below).

Figure 2: AI-assisted correlation matrices of agreement (left) and disagreement (right)

We then convert these matrices into comprehensive feature vectors for each respondent and apply agglomerative hierarchical clustering to identify natural expert groupings representing distinct perspectives. The clustering results are visualized through dendrograms showing response similarity structures. Additionally, we apply UMAP to project these feature vectors into two-dimensional space, creating intuitive visualizations of expert clustering patterns color-coded by their expertise domains.

For qualitative analysis, we implement a systematic four-dimensional approach using specialized Claude prompts to analyze each question:

- Quality Analysis: Critical assessment of response patterns and methodological soundness

- Consensus Analysis: Identification of explicit and implicit points of agreement

- Disagreement Analysis: Nuanced interpretation of meaningful divergences

- Gaps Analysis: Recognition of conceptual omissions and emerging novel ideas

Finally, we synthesize quantitative clustering with thematic content analysis to generate comprehensive reports that map identified expert clusters to their characteristic themes, explaining how different groups approach the questions and identifying conceptual bridges between seemingly disparate perspectives.

Delphi study process

- Round 1: Initial Survey

- Experts respond to open-ended questions regarding EPEEs, including their differentiation from psychopathology, support needs, and assessment criteria.

- Responses are analyzed using AI-assisted thematic analysis.

- Note: All round 1 survey questions underwent pilot testing with 2-3 domain experts external to the panel, to confirm question clarity and appropriateness. Feedback from pilot testing informed necessary refinements before survey distribution. The questions developed for subsequent survey rounds will be discussed in collaboration with experts external to the panel prior to distribution, rather than piloted.

- Consensus is measured through correlations between expert responses, which is used to formulate the subsequent round of questions.

- Round 2: Refinement of Ideas

- Participants review a synthesized summary of Round 1 findings, providing feedback on emerging consensus and unresolved disagreements.

- Focused questions are introduced to clarify key points of divergence and explore potential frameworks for clinical classification.

- Consensus is measured through correlations between expert responses, and through participant agreement with specific conclusions from round 1.

- Consensus and divergence measures are used to formulate subsequent rounds of questions.

- Round 3: Final Consensus Building

- Participants rate the importance and feasibility of proposed clinical guidelines.

- Discrepancies are further addressed, and a final round of synthesis is conducted.

- Consensus is measured through correlations between expert responses, and through participant agreement with specific conclusions from round 2

- Consensus and participant feedback are used to formulate final recommendations.

- Final Quantitative Consensus Survey

- Experts complete a brief survey assessing their level of agreement with the formulated recommendations.

- Consensus is defined as 75% agreement (indicating either “agree” or “strongly agree” on Likert scale) for each conclusion (cf. Diamond et al., 2014).

To maintain objectivity in the consensus process, members of the research team and steering committee do not have voting rights in any Delphi survey rounds. The research team role is limited to designing the methodology, analyzing responses, and facilitating the process rather than contributing to the expert consensus itself.

Qualitative study pre-registration can be found at: https://osf.io/3esyx/

Study questions

Copies of the questions asked in each round can be found below:

Round 1: Link to Round 1 survey questions

Round 2: Link to Round 2 survey questions

Round 3: Link to Round 3 survey questions

Final agreement: Link to quantitative agreement rating questions

Current status

Study completed October 2025. Preparation of full compendium of results underway.

Research team

Dr. Daniel M. Ingram, Co-Principal Investigator

Dr. Hannah Biddell, Co-Principal Investigator

Beata Grobenski, Research Associate

Reed Bender, Data Analysis

Steven Egan, Project Manager

Preliminary results

The complete compendium of study results are currently being compiled. If you wish to receive them when available (expected in November 2025), you can send an email request to eop@ebenefactors.org.

Preliminary results from the final quantitative agreement ratings are detailed below.

In the final quantitative agreement survey (n=19), participants rated their agreement (6 point strongly disagree to strongly agree scale), across 97 statements organized into eight main areas:

- Engagement – Initial therapeutic contact and relationship building

- Assessment – Differentiating emergent phenomena from medical conditions while prioritizing functional impact

- Risk Assessment and Safety Planning – Balancing collaborative approaches with protective interventions when imminent safety concerns arise

- Acute Care – Immediate interventions for crisis situations and stabilization

- Long-term Care – Ongoing treatment approaches that support integration and sustained wellbeing

- Professional Standards – Therapeutic competencies for clinicians encountering emergent phenomena in practice

- Specialization and Training – Specialized qualifications for clinicians working regularly in settings where emergent phenomena are common

- Healthcare System Integration – Organizational and policy implementation needed to support emergent phenomena within existing healthcare structures.

Consensus (>75% respondents either agree or strongly agree) was achieved on 86% of statements. All statements that reached consensus are listed below.

Glossary

Based on expert feedback, we have developed a glossary of key terms used in preliminary statements throughout the Final round survey.

Note: Definitions in this emerging field continue to evolve, and these working definitions aim to facilitate shared understanding rather than impose rigid boundaries.

Relevant research publications

- Ataria, Y., Dor-Ziderman, Y., & Berkovich-Ohana, A. (2015). How does it feel to lack a sense of boundaries? A case study of a long-term mindfulness meditator. Consciousness and Cognition, 37, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.09.002

- Britton, W. B., Lindahl, J. R., Cahn, B. R., Davis, J. H., & Goldman, R. E. (2014). Awakening is not a metaphor: the effects of Buddhist meditation practices on basic wakefulness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1307, 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12279

- Cooper, D. J., Lindahl, J. R., Palitsky, R., & Britton, W. B. (2021). “Like a Vibration Cascading through the Body”: Energy-Like Somatic Experiences Reported by Western Buddhist Meditators. Religions, 12(12), 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121042

- Corneille, J. S., & Luke, D. (2021). Spontaneous spiritual awakenings: phenomenology, altered states, individual differences, and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720579

- Horton, P. C. (1973). The mystical experience as a suicide preventive. American Journal of Psychiatry, 130(3), 294-296.

- Kornfield, J. (1979). Intensive insight meditation: A phenomenological study. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 11(1), 41.

- Lindahl, J., Kaplan, C., Winget, E., & Britton, W. (2014). A phenomenology of meditation-induced light experiences: traditional buddhist and neurobiological perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00973

- Lindahl, J. R., & Britton, W. B. (2019). “I have this feeling of not really being here”: Buddhist meditation and changes in sense of self. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 26(7–8), 157–183.

- Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K., & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PloS one, 12(5), e0176239.

- Luhrmann, T. M., Dulin, J., & Dzokoto, V. (2024). The shaman and schizophrenia, revisited. Culture, medicine, and psychiatry, 48(3), 442-469.

- Lukoff, D. (2007). Visionary spiritual experiences. SOUTHERN MEDICAL JOURNAL-BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA-, 100(6), 635. https://www.imprint.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Lindahl_Open_Access.pdf

- Masci, D., & Hackett, C. (2018). Meditation is common across many religious groups in the US.

- Milliere, R. (2020). Varieties of Selflessness. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 1(I), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.33735/phimisci.2020.I.48

- Millière, R., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Trautwein, F.-M., & Berkovich-Ohana, A. (2018). Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475

- Nicholson, P. T. (2014). Psychosis and paroxysmal visions in the lives of the founders of world religions. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 26, E13–E14. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12120412

- Sandilands, O., & Ingram, D. M. (2024). Documenting and defining emergent phenomenology: theoretical foundations for an extensive research strategy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1340335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1340335

- Sparby, T., & Sacchet, M. D. (2024). Toward a Unified Account of Advanced Concentrative Absorption Meditation: A Systematic Definition and Classification of Jhāna. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02367-w

- Vieten C, Wahbeh H, Cahn BR, MacLean K, Estrada M, Mills P, et al. (2018) Future directions in meditation research: Recommendations for expanding the field of contemplative science. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0205740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205740

- Wright, M.J., Galante, J., Corneille, J.S. et al. Altered States of Consciousness are Prevalent and Insufficiently Supported Clinically: A Population Survey. Mindfulness 15, 1162–1175 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02356-z

Get involved

Learn more about us

The Expert Opinion Project, supported by Emergence Benefactors, is part of the White Paper of the Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium (EPRC). To learn more about the EPRC visit here:

The Emergent Phenomenology Research Consortium (EPRC) and our mission

Learn more about the next steps for the Expert Opinion Project

Donate

Donate to Emergence Benefactors (US 501(c)(3) charitable organization)

Find us on social media

Send us an email

FAQs

- What are emergent phenomena?

Emergent phenomena, experiences and effects (EPEEs) are experiences often interpreted or labelled as spiritual, mystical, energetic, psychedelic, or magical in nature (see Sandilands & Ingram, 2024 for extended definition) that may lead to transformative outcomes and be more prevalent than previously thought. For example, Wright et al. (2024) found that 45% of participants in a general population study reported experiencing non-pharmacologically induced EPEE at least once in their lives, with higher rates under the influence of mind-altering substances.

According to Sandilands and Ingram (2024), these experiences include but are not limited to:

- deep absorption states (Sparby and Sacchet, 2024),

- energy-like somatic experiences and involuntary movements (Cooper et al., 2021),

- shifts to body schema (Ataria et al. 2015),

- heightened basic wakefulness (Britton et al., 2014),

- endogenous light perceptions (Lindahl et al., 2014),

- visionary experiences (Lukoff, 2007),

- profound altered states resulting in emotional, behavioural, existential, ontological and paradigmatic shifts, such as deep changes to sense of self and one’s connection to the universe (Corneille and Luke, 2021; Lindahl and Britton, 2019; Millière et al., 2018; Millière, 2020) and profound vocational and life-trajectory impacts (Nicholson, 2014).